Note: Throughout this post, I’ll use “us”, “I”, “me”, and “we” fluidly, since I did most of these things with my friend, and I just can’t decide whether each thing was done by me alone, or together with my friend.

When I was in grade 8, I started a bulletin board (BBS) on my family computer, using a 2nd phone line that I convinced my parents to get for us. It started out as a text-based system using free software that I downloaded from another BBS, but I soon migrated to graphical systems.

I used a pirated version of First Class Server for experimentation. First Class was the gold standard for Mac BBS software, but it was quite expensive. I recall that it was like $300 for a hobby license, which had a limit of 100 user accounts, and you couldn’t use it for commercial purposes. I might be misremembering the exact price and limitations, but for a kid with no job it was champagne, and I wasn’t even old enough to have a beer budget yet.

The thing that set First Class apart from all the competition was its graphical user interface. You see, most BBSes at the time were text-based, meaning that it was kind of like using your terminal program. No mouse, or windows. The menus would just be numbered lists of options, and you would have to type in the option that you wanted to choose. I happily tolerated these archaic text-based interfaces until I discovered First Class.

First Class provided, pardon the pun, a “first class” experience. When you logged into a First Class BBS, it felt like you were just accessing a multi-user part of your computer. The main menu was just like a regular Finder window but with some custom icons and backgrounds in the window. It supported email, message forums, file attachments, multi-user chat-rooms, and background, resumable file downloads. The experience was pretty darn close to modern systems like Slack and Discord – but back in 1993, it was ground-breaking.

For me, there was no going back to text-based bulletin boards, once I knew that GUI BBSes existed.

The only problem was cost. First Class was out of my price range, and using pirated software for a public BBS just wasn’t an option – it was too easy to get caught. And it was always my intention to grow it into something big, like AOL or Compuserve, so everything had to be legitimate and above board.

Luckily, in chatting with the sysop of The Revelation, the best First Class BBS in the Vancouver area at the time, I discovered that they had a license for NovaLink Pro, a competing BBS system that also had a graphical user interface. And he was willing to sell it to me for an affordable price. It was around $100. I think it had a limit of around 100 users, but there was no commercial restriction.

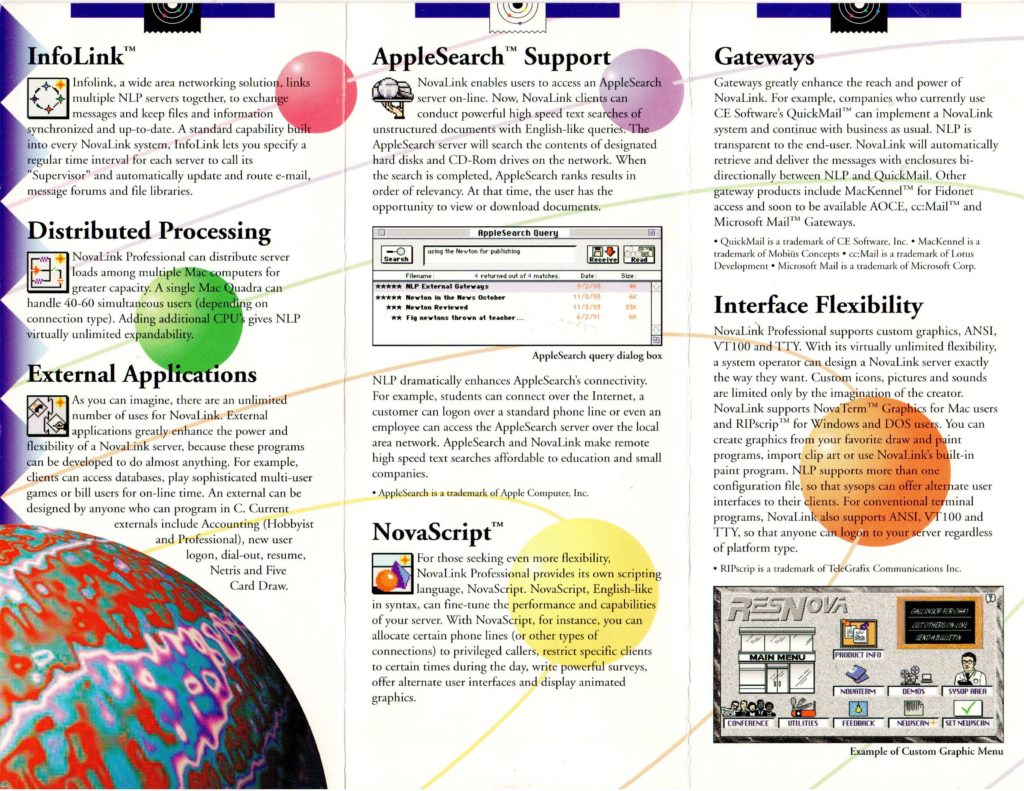

I had never heard of NovaLink Pro before, but it sounded perfect. There weren’t any NovaLink Pro BBSes in my area, so it was difficult to make a comparison, but they had a demo version that I downloaded and installed. It wasn’t as polished as First Class. Some aspects of the UI were similar. E.g. The main menu looked like a finder window with icons for all of the menu items. However, in First Class, you could customize the look of the items – change the icons, drag them into different positions, etc. On NovaLink, the icons were arranged in a grid, and sorted alphabetically, and you couldn’t change the config. You could click on an icon to select it, or double click it to open it, but you couldn’t drag it around.

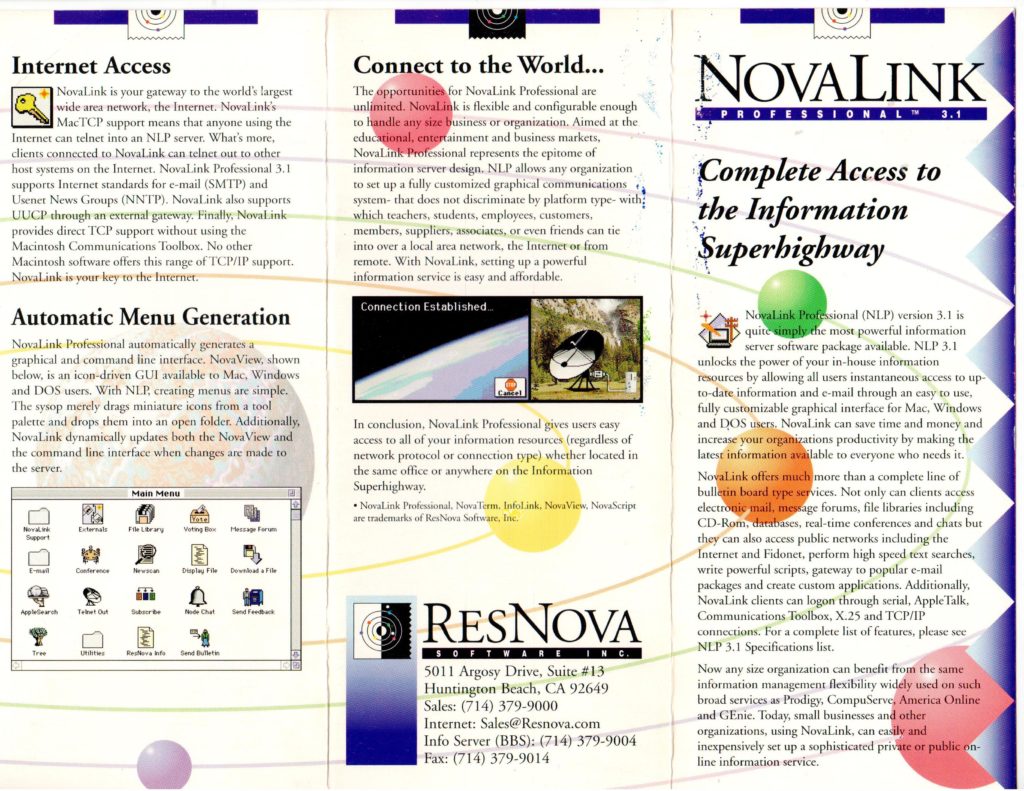

NovaLink did have some cool features that First Class was lacking, such as Telnet support (i.e. the ability to log into the BBS over the internet – which was a very new thing), but overall, the impression I got was that it was a poor-man’s First Class.

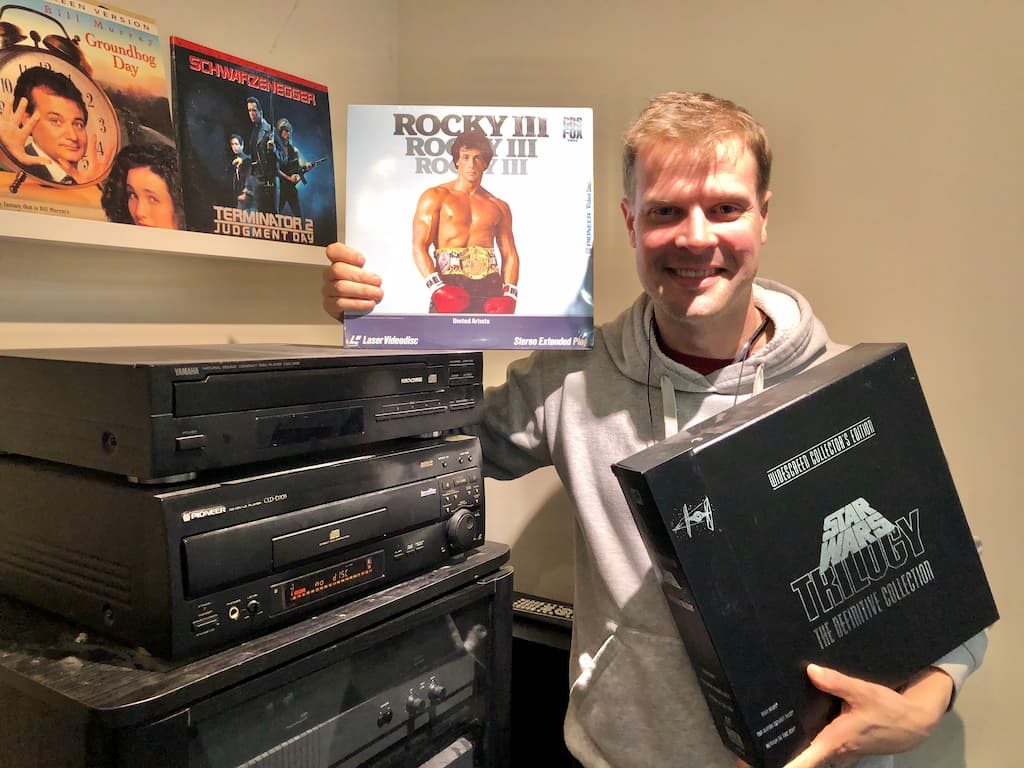

As a fourteen-year-old kid, I was nothing if not a “poor man”, so I felt that NLP (NovaLink Pro) was a perfect fit. There’s also some part of me that likes to support the “B” team. I was a Macintosh user in a world of 99% PC, and despite owning a Nintendo Entertainment System, I was very curious about competitors like the Sega Master System – and later on, about the “also-rans” in the 16-bit console wars, like TurboGraphix16. My search for movies similar to Indiana Jones led me to a few duds (King Solomon’s Mines, Alan Quaterman and the Lost City of Gold), but also to a few that were better than okay (Romancing the Stone).

So, in the world of GUI BBSes, where First Class was the clear leader, I liked the idea of going with NLP – the underdog.

Before finalizing the purchase, I contacted ResNova, the company that made NLP to make sure that it was “legal” for them to sell me the license. They said it was, but recommended that I buy the manual from them – and we would be entitled to upgrade to their new version, “4.0”, when it came out.

I bought the software from the Revelation BBS, but I don’t recall ever receiving any packaging from them. It must have been the sort of thing where they called ResNova to transfer the license. I do recall having an option of how I wanted to get the software. I could either wait for it to come by mail (actually that part was going to happen anyways, because we bought the manual – and the software came on floppy disks inside the manual), or I could download it from Nova Central, ResNova’s BBS, and pay the long distance fee. Yes, in those days, before the internet, you actually needed to dial into BBSes over the phone, and if the BBS was in a different area (ResNova was located in California), then you had to pay long distance fees by the minute, which could grow to be substantial.

I figured, how long could it possibly take to download the software? I was also pretty hyped about logging into a real BBS that used NovaLink Pro, so I chose to try to download it.

As it turned out, it can take a very long time to download software. The application fit onto three 1.44MB floppy disks, so it was probably about 4 megabytes. My modem was 14.4kbps, so under optimum conditions, it should take about 100 seconds per disk, so I should have been looking at five minutes or so. I don’t remember the long distance prices, but let’s say they were ten cents per minute (I think that is realistic for the time), then I’d be looking at fifty cents. Well within my budget. But there was still the matter of logging in, and filling in the sign-up form. So we’re looking at about ten minutes or so. I could splurge for a dollar. Heck, make it twenty minutes – I’ve got plenty of change where that came from.

Unfortunately, their download protocol, a custom protocol that they named RNP (for ResNova Protocol) was a little flakey. I started downloading the disk images for the software, and then proceeded to browse around the BBS to see what else they had to offer. Unfortunately, the download stalled at around 5%. I gave it a few minutes to see if it would “un-stall” itself, and after it didn’t show any more progress, I canceled the download and started again. The same thing happened again. So I put it on for a third time, but this time I decided to just let it download undisturbed and not browse around the site. Their download protocol, a custom protocol that they called RNP (ResNova Protocol) was supposed to support background downloading, but it was a little flakey.

I don’t think that three times was a charm, because I remember the call lasting nearly three hours. Ultimately, though, I did manage to download the software. I didn’t mention anything about the long distance to my parents, and they never brought it up, so I’m guessing it wasn’t so high as to stick out like a sore thumb.

Two weeks later, I received a parcel in the mail with a hard copy of the manual, printed and bound in a three-ring binder, and “official” install disks. There were four disks in total, the fourth one containing only my license key.

Setting up the BBS

I installed the BBS on the family’s Macintosh Centris 660AV computer, and just kept it running in the background all day. As I write this, I begin to question how well this would have worked on the Macintoshes of the day – I think it was around System 8, which didn’t have preemptive multitasking. But as far as I recall, it worked just fine, and my family didn’t even know it was running in the background.

I had a lot of fun poring over the manual to learn about all of the features. NovaLink Pro was a hybrid Text/GUI system that clearly used to be text-only, and added a graphical UI later on, evidenced by the fact that many of the features, such as scripting, were text-only, and had no impact on the GUI.

One of their big selling features, which supposedly set them apart from First Class, was that they supported Telnet out of the box – i.e. users could connect to the BBS over the internet, potentially opening it up to a global audience. Unfortunately, this was one of those “text-only” features. Yes, they could log in over the internet, but they could only use the text interface. That wasn’t of much interest to me.

My plan for the BBS was mostly to provide message forums and file download areas, but I also wanted to create a visually appealing experience, using The Transformers (the toy) as a theme. Most First Class BBSes provided a “modded” version of the client with some custom icons and background images, which gave each BBS a distinctive look and feel. These mods were easy to make using Apple’s free ResEdit tool. I created one of my own when I was experimenting with First Class, prior to purchasing the license for NLP.

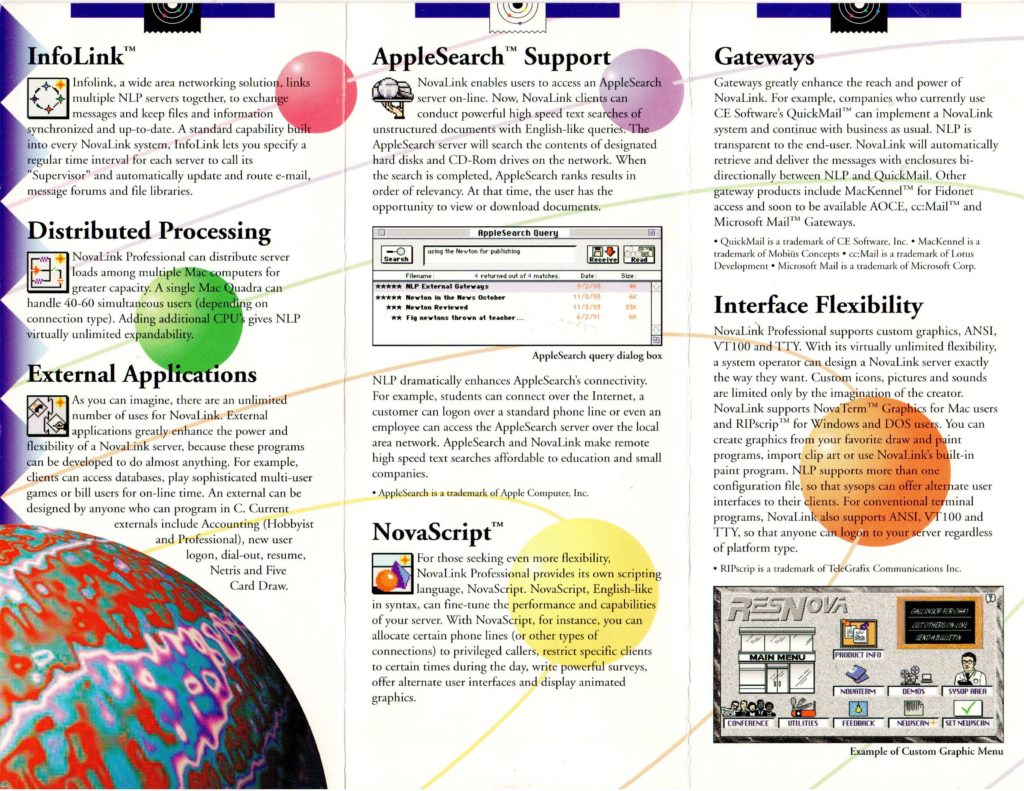

I was a little disappointed when NLP didn’t seem to allow the same kind of customization. The administration app included a menu editor tool that allowed me to drag items, such as file libraries, message forums, and chat rooms from a palette into the menu, but it didn’t provide any layout options, nor did it allow me to customize the icons. It always laid out the icons in a grid, in alphabetical order.

They did provide an option to use a custom graphic with hot-spots for menu items which was quite cool, but it was an all-or-nothing proposition, at least on a per menu basis. I.e. For a given menu, you could either use a custom graphic, or you could use an automatic menu, but you couldn’t, for example, use a custom graphic in the background, and use the auto-layout icons in the foreground.

It took a while to get used to this limitation, and, in some ways, this was better than the First Class method of modding the client with ResEdit. For example, users didn’t have to download a custom client to be able to see my board’s custom graphics. The vanilla client supported it out of the box. If I added a menu with custom graphics, it would be instantly available to all clients. It was common practice, by contrast, for First Class BBSes to periodically update their clients with new graphics from time to time, and advise users to download their latest version. The NLP solution for custom graphics was much closer to the way that that web would later work.

And, hey, it was actually kind of fun to make menus in photoshop.

Reading the Brochures I’ve always been a sucker for reading brochures. As a child, I spent hours on my bedroom floor thumbing through the pages of the Sears Wish Book, imagining that I was the little boy depicted playing with the GI Joe aircraft carrier, or riding on that CHiPs-themed Big Wheel. Fast forward ten years, and things hadn’t changed much. Only replace the Sears catalog with ResNova’s brochures for NovaLink Pro.

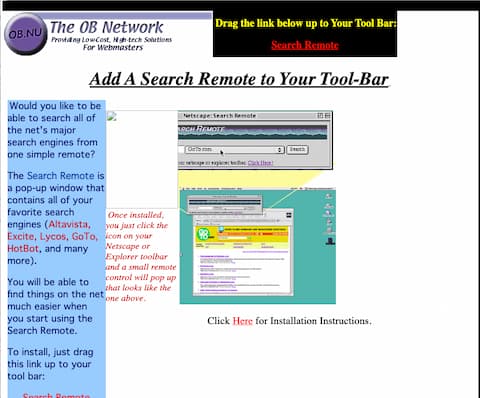

I don’t recall if the brochures came with the software when I purchased it, or if we received them prior to the purchase, but I do remember spending many hours studying them, and memorizing all of the features listed. Features like Telnet, Usenet, Fidonet, and Apple Search. I only had a dim idea of how the features worked, but where experience and know-how were lacking, my imagination filled in the gaps. I imagined building a service like AOL, where hundreds or thousands of people in the Vancouver area would log in to my BBS to get their news, access the internet, chat with each other, and maybe even buy products.

In fact, I even made my own brochures for this yet-to-be-created online service, which I dubbed “Vancouver Online International” or VOI for short. I guess “Prime Time BBS” just wasn’t grand enough for my vision. I spent hours, days, weeks creating mock-ups for each section of the BBS in Photoshop, making use of all of the modern effects it offered. Lots of emboss, gradients, lens flares, and, my favourite: extrudes. That’s the one where it partitions the image into 3D cubes that are sort of jumping out of the image at you.

The World Wide Web is Coming

The press releases were almost as exciting as the brochures, despite their lack of graphics. I distinctly remember the one announcing NovaServer 4.0. Yes, they were changing the name of the server from NovaLink Pro to NovaServer for their next major release. The big news, in addition to the name change, was that it would include full support for the World Wide Web.

This was the first time I had ever read (or heard) the term World Wide Web, or WWW, and frankly, it didn’t mean much to me at the time. I recall being a little bit disappointed by the announcement because I was more hoping that they would add FTP support, since this was the key to file downloads. Nonetheless, I was intrigued by this new “Web”, as they called it.

As soon as NovaServer 4 was available, I downloaded the demo, and started playing with it. The WWW support was neat, but clearly nascent. The client came with a reasonably compliant web browser built into it, and it used HTML to encode most of its custom graphics, but the general web browsing experience left a lot to be desired. For one, it didn’t support file downloads at all.

Despite its shortcomings, I recognized the potential.

And Then They Were Gone

Nova Server’s inclusion of a Web Browser inside a Bulletin Board client is, perhaps, the most direct link between the golden age of the BBS and the advent of the internet. No other BBS software, that I’m aware of, incorporated the internet to the same degree as Nova Server did. Unfortunately, it barely got a chance to spread its wings before it was purchased by Microsoft and discontinued.

From Web TidBits, Nov. 1996:

Microsoft Gets Personal — In a surprising move, Microsoft and ResNova announced that Microsoft has acquired ResNova’s Web server products: the personal Web server WebForOne, and the full-featured Boulevard. In conjunction, five of ResNova’s employees, including president Alex Hopmann and product manager Lauren Antonoff, have joined Microsoft’s Internet Platform and Tools division in San Jose, and ResNova is seeking a buyer for its NovaServer bulletin board system.

http://www.resnova.com/

I only discovered this years later. From my perspective, ResNova just sort of disappeared without a trace. Even now, with the benefit of modern search technologies like Google and Bing, it is quite difficult to find corroboration for my memories of its existence. You can find the odd mention of it on old BBS lists that people have posted, and I found one press release on a Usenet archive – though without the ResNova letterhead, it’s not the same. The best proof of life for NovaServer is found in the December 1995 issue of BBS magazine, which archive.org has kindly preserved for humanity. Link here (page 46).

More recently I discovered that Apple Fritter, currently uses NovaServer 4 for its eWorld clone.

Reviving Nova Server

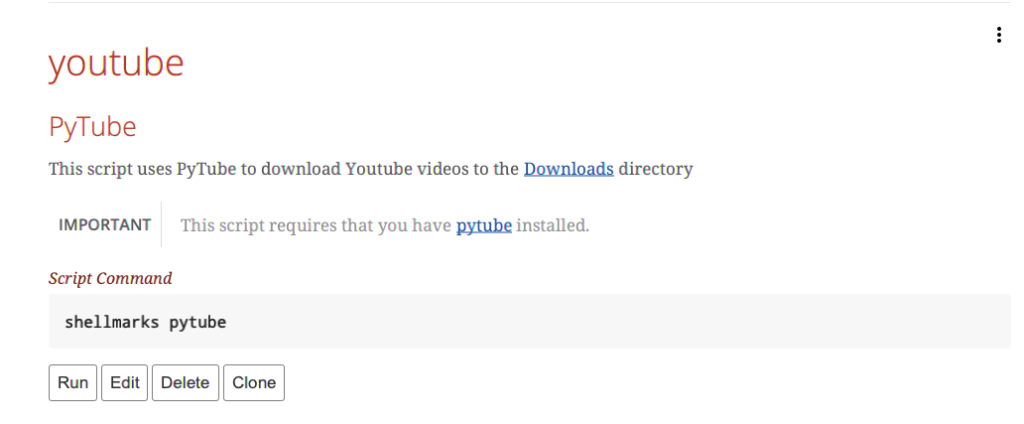

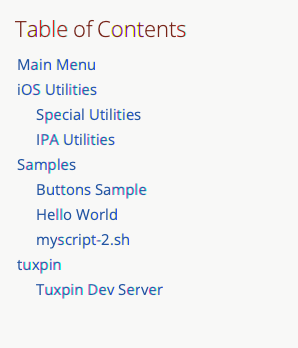

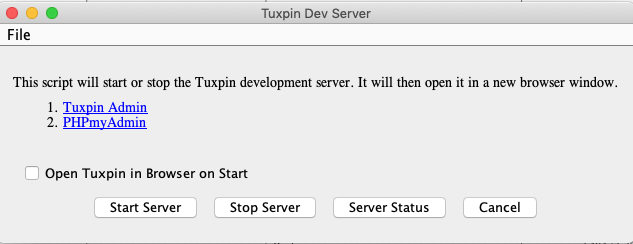

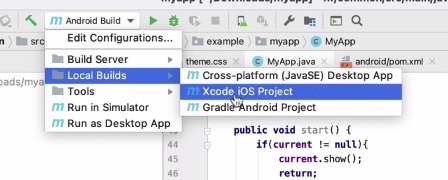

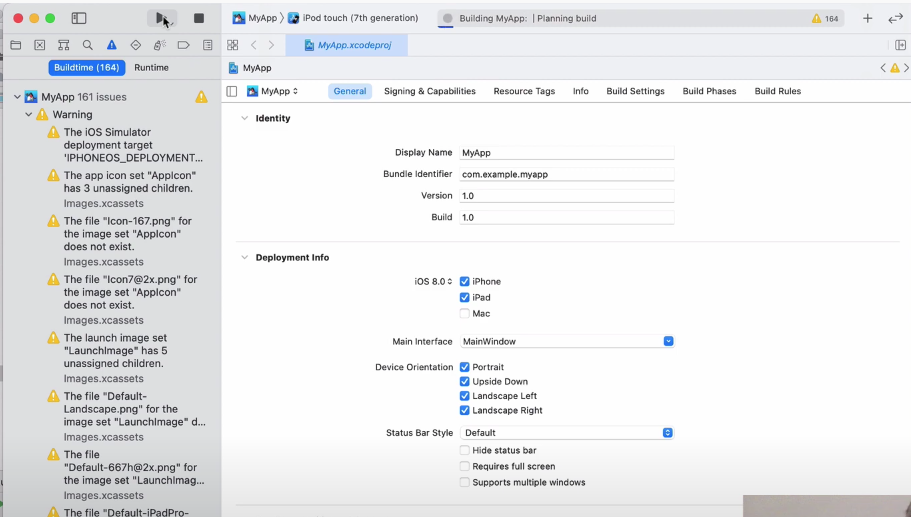

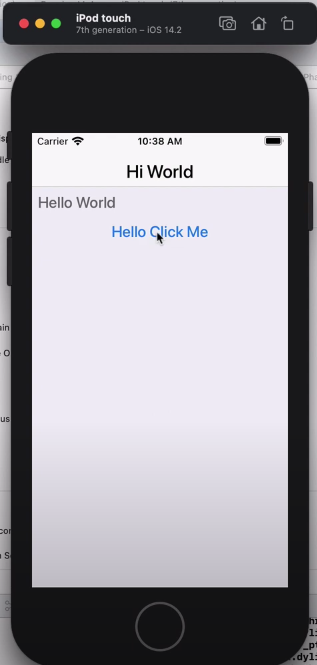

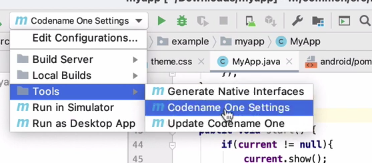

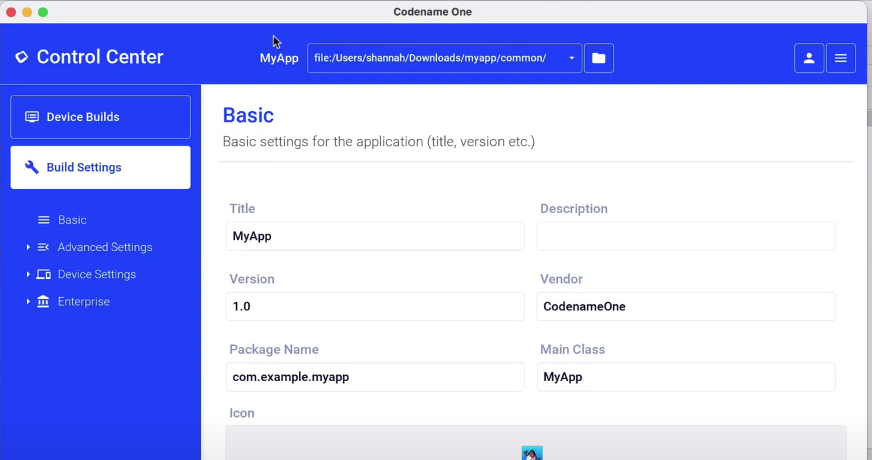

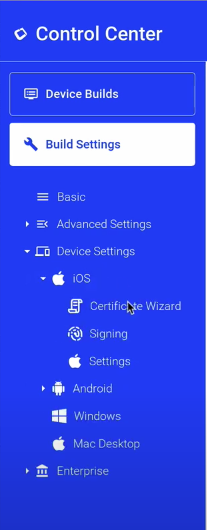

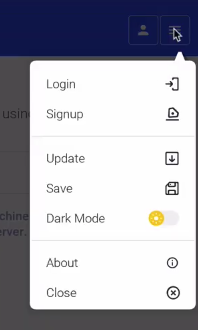

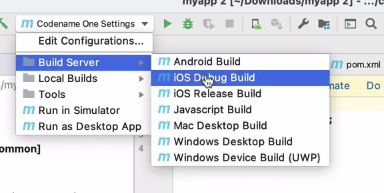

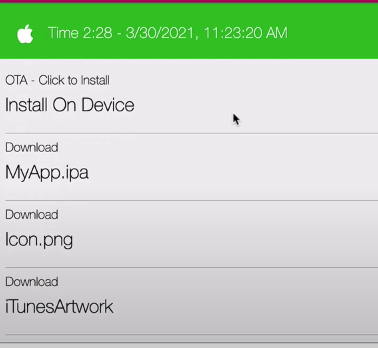

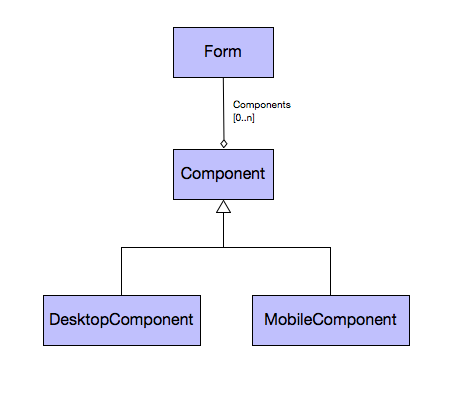

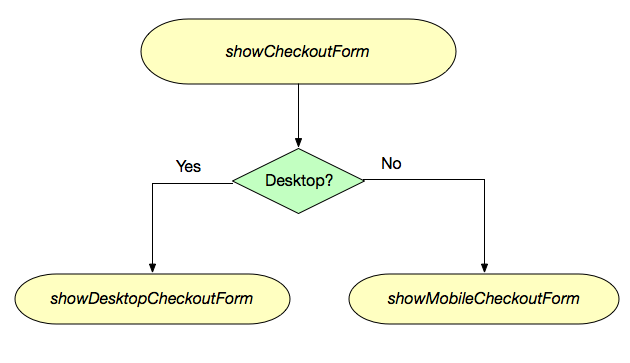

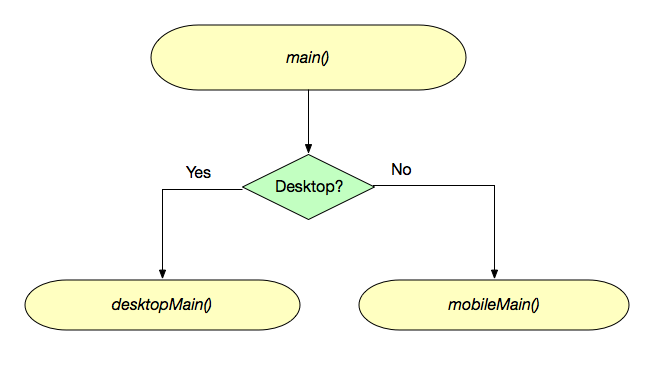

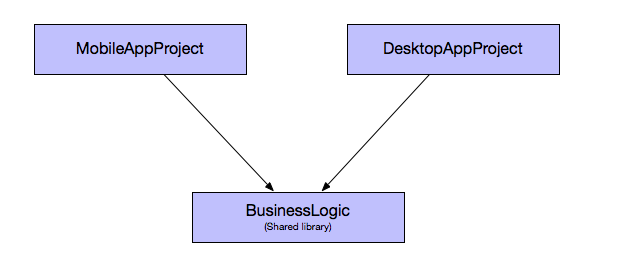

In my spare time, I still sometimes play with Nova Server, and I have dreams of reviving it. A couple of years ago I managed to create mostly-functional web, mobile, and desktop clients. I still have all the old software, and have acquired some documentation for its C API for writing extensions, which should make it possible to write a CGI gateway, which would really open things up. E.g. I could write dynamic extensions using PHP, Python, or any other modern programming language, to augment the features of the old Nova Server.

I don’t know when I’ll have time to do all of this tinkering between the day job and the family, but I choose to believe that someday I’ll have the time, and, God willing, still have the passion to build things like this. In the meantime, I’ll just wax nostalgic about the good ol’ days, when the internet was still mostly just a dream, and we could build it into anything we wanted.